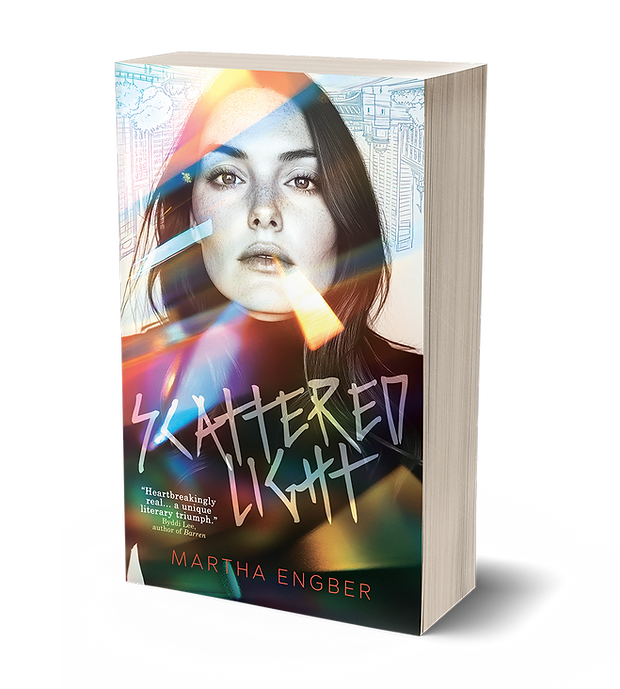

Scattered Light

FREE Excerpt

Book I

“There is always light. If only we’re brave enough to see it. If only we’re brave enough to be it.”

Amanda Goodman

Tues., April 13, 1999

Mary pulled open the door of Herzl’s sandwich shop and inhaled the yeasty, salty smell of fresh bread and pickles. Though long after the popular noon lunchtime, people still packed the tiny Chicago storefront. Fortunately only five people stood in line, the last a very tall Black man. Mary stepped behind him. Her stomach audibly growled, but she happily ignored all such discomforts. Not only did today mark her thirty-sixth birthday, but she had just received news that made her a certifiable badass who’d finally earned herself a financial and professional throne so high no one could pull her down. At least not easily.

She glanced back. Seeing no one behind her, she slipped out of line to visit the refrigerated drink case. She pulled out a Dr. Pepper—a blast from her high school junk food past—and feeling extra decadent, plucked a bag of Cheetos from the chip pile. She got back into line behind the tall man.

He wore an expensive suit, shiny gray as the wet sidewalk outside on this blowy, rainy April Tuesday. The expanse of cloth across his back felt somehow soothing, like standing on a pier and letting your eyes wander the breadth of Lake Michigan. The quiet of the color made her accomplishment come into sharper focus. Two hours ago, Judge Doxon had certified the class action lawsuit Mary filed on behalf of a workers’ union health fund. The case involved thousands of Grayson Foods employees. The twenty-one reported job-related deaths and hundreds of injuries pointed to the kind of corporate greed and racial discrimination that could potentially lead to a huge settlement. The kind of lawsuit her Chicago Tribune reporter friend would term a sexy story.

She could almost hear her brother, Danny’s, voice. Way to go, Mar.

Her skin tingled with equal parts excitement and terror at the mammoth task ahead of her. Yet the size of the endeavor guaranteed lots of work, monetary security and almost certain promotion to managing partner. When she finally reached that level, she would be set for life. Then again, she’d predicted that kind of fail-safe surety a number of times, only to have another obstacle push her back from her goal: to escape the failure of her youth.

But this time—this time—her professional success and financial stability would be assured.

Maybe.

A gently-curled end of her strawberry-blonde hair fell forward over the lapel of her London Fog raincoat. Soon as the brand name popped to mind, she smiled, knowing Danny would tease her about buying expensive clothes, so far from her ragged jeans and concert T-shirt days. But after razzing her, he would tell her she looked classy, a comment she’d love, but nonchalantly wave off. There’d be no reason to tell him that in truth, she couldn’t break the frugal habits she’d developed in her without-money youth. She couldn’t bring herself to buy anything at full price. The raincoat and the black Hermes messenger bag, the Calvin Klein suit and Gucci shoes—all had come from thrift stores, consignment shops or the sale rack at Marshall Field’s.

“Sarah!” Joe Herzl yelled from where he stood behind a counter beneath a PAY HERE sign.

A teen girl picked up a tray of food from the counter and moved to a table with three other girls, all of them wearing red plaid Catholic school uniforms. Mary stepped forward as the line of customers advanced. She looked over the tall man’s broad shoulder to the Don’t kvetch, nosh! sign above the glass deli case. She started a mental to-do-list for when she got back to her office.

Her office.

Even now the phrase brought a rush of pleasure, strong as the day she officially joined the forty-lawyer firm in the Board of Trade building, one of the most famous structures in Chicago. She got the job after passing the Illinois Bar. And before that, graduating from the University of Chicago Law School. And before that, rocking two summer internships. And before that, getting her undergrad at the University of Illinois Chicago. And before that, earning her high school GED while still technically a junior in high school.

And before that—

She abruptly lifted her chin. She would not go toward those dark thoughts. Not on her birthday. She diverted her eyes to the framed photos of celebrities and politicians who had eaten here: Mayor J. Daley, Frank Sinatra, current president Bill Clinton. A scent drifted into her subconscious, the smell so subtle she found herself inhaling deeper. The fragrance smelled like damp wood from a place she’d never been. She exhaled silently, somehow deeply startled. Then she leaned toward the man’s back to inhale again. The scent smelled so opposite to the aftershave of the men she’d dated over the years. Less macho-guy-trying-to-overtake, more gentle.

She looked up at the man’s back. Hands in his pockets, he held his closely-cropped head high, as though still perusing the menu above the deli case. She wondered what he’d order.

“Charlie!” Joe called.

Chair legs scraped on the tile floor. Mary tucked her soda can under her left arm and the chip bag between her teeth. Having freed both hands, she fished in her messenger bag for her wallet. Ignoring the token sum of cash she kept to satisfy muggers, she selected the Herzl’s discount card from the collection of such cards stuffed in the plastic sleeves. Her fully stamped card meant this birthday sandwich would be free.

The line advanced. The tall man stepped up to Joe’s wife, Sandy, a rotund woman wearing plastic-frame glasses almost as red as her dyed hair. She stood beneath an ORDER HERE sign.

In a contemplative way, the tall man said, “I will have …”

By his accent, the absence of a contraction and the way he flipped the ending of the L in will, he clearly came from somewhere overseas. And how cool to have a lilt that made you sound elegant, maybe even when you cursed.

“… the Dutch crunch roll, please,” he said.

Mary nodded, the man having gotten off to a good start. All great sandwiches begin with bread sturdy enough to hold everything together. The kind of bread you had to tear with your teeth and chew with gusto. Gusto being a term her friend, Kathleen, might use.

“And please add a little pepper and garlic aioli,” he said.

And how smart of him to shun mayo, or for that matter, horseradish or mustard, all of which could overwhelm the various flavors. And though aioli had always struck her as a bit froufrou, the spread did moisten the experience without setting your mouth afire.

“The roast beef,” he said, “sliced extra thin.”

Mary smiled because this man was clearly a contender, a thinker, someone who considered the smallest of details. Not too many people knew to ask for extra thin meat. Which provided more surface area. Which, when combined with air pockets in the bread, allowed the various flavors to seep in.

“Swiss cheese,” the man said.

Exactly! Swiss instead of the too-sharp asiago or too-greasy cheddar.

“And some parmesan,” he said.

A twist! One she’d never considered but that struck her as brilliant. In the final toasting of the sandwich, the parmesan would create a lovely, crunchy crust atop the meat. If, that was, he chose to toast his sandwich.

“Toasted?” Sandy said.

“Yes, please.”

Mary nodded as though she was again fifteen and someone had handed her front-row tickets to Pink Floyd. Fucking A!

But life being life, the other shoe must always drop. She braced herself for disappointment from the tall man.

But then he said, “And grilled onions and mushrooms.”

Mary wanted to laugh aloud because the man had just achieved the sandwich equivalent of a ton 180. Only three times in her amateur dart-throwing life had she achieved the feat of landing three darts in a triple twenty, earning max points for a round.

“Is that all?” Sandy said.

When the man hesitated, Mary couldn’t help herself. Not when he stood so close to winning her heart.

She leaned forward to get within the man’s peripheral view.

“You should get the grilled peppers, too.”

He glanced sideways at her, eyebrows lifted above his brown eyes. Maybe forty, he had a round face of high cheekbones and full lips.

He said, “The peppers are delicious?”

“Yup,” Mary said, “because they mix the green with the red. Tart with sweet.”

“Like life.”

Now Mary looked surprised. She came from a crass background where whoever attempted such witty repartee would be mercilessly ridiculed. Whereas she’d learned to appreciate such lingual subtleties from Mr. O’Brien, her high school English teacher.

She smiled. “Exactly.”

“Mary loves our peppers,” Sandy said.

“Well if Mary loves the peppers, then please add peppers,” the man said.

“Is that all?” Sandy said.

“And a Yoo-hoo,” the man said.

And a Yoo-hoo!

Mary didn’t know anyone who liked the chocolate-flavored drink, but he smelled and acted like a prince and so deserved at least one eccentricity.

Mary started to explain he had to get his own drink, but decided she’d be faster. She pulled a Yoo-hoo from the drink fridge and handed him the can, which he accepted with his left hand, one that didn’t wear a wedding band, though of course he could still be married. If so, what did she care? They were just two people standing in line, for god’s sake.

“Good choices,” Mary said, “regarding the sandwich. You won’t be sorry.”

When he smiled, she had the strange sensation of drinking sweet tea, the kind people brought when you were sick and that made you feel better.

“What’s your name, hon?” Sandy asked the man.

“Damba.”

Dom-ba.

“What was that?” Sandy said, cocking an ear against the noise of talking people.

“Like Dumbo,” he said, “except with two As.”

Sandy looked down at her pad for a moment, perfectly still.

Then she nodded once, a karate chop. “Got it. For here?”

“I—” He glanced at Mary.

Mary stared at him, chin slightly tucked in the way of, You got one chance, man. Normally she used her lunch break—when she actually took one—to be alone for a while. But today she felt like sharing the strange happiness and security she felt at this exact moment; a combination of birthday fun, professional win, and funny, yet oddly sexy, sandwich flirtation.

He smiled at Mary. “For here.”

Mary smiled too.

“What’ll you have, Mar?” Sandy said. “The usual?”

“Exactly what he had.”

“With the parmesan?” Sandy said, leaning her shoulders back at the deviation in Mary’s order.

Mary laughed. “Yeah. It’s my birthday and I’m being wild.”

“Mazel tov!” Sandy said. She slipped both orders to her nephew. The young man glanced shyly at Mary even as his hands flew while filling orders he then slid to Joe, who called the name on the order.

Mary nodded at Damba. “Let’s get out of the way.” She signaled for him to move toward Joe at the register.

When Damba pulled his wallet from inside his suit coat, Mary placed her discount card on the counter and told Joe, “I get a free sandwich today. I want to give it to him.” She looked at Damba. “Every time you come, they stamp your card. If you come twenty times, you get a free sandwich.”

“I—” Damba said.

Expert at avoiding awkward thank-yous for tiny acts of goodwill, Mary interrupted to tell Joe, “Can you give him a loyalty card? And I need a new one.”

Joe handed a card to each of them.

“And today is free for Mary,” Sandy said to Joe. “It’s her birthday.”

“Mazel tov!” he said.

“No, no.” Mary shook her head vigorously. “I’m paying for mine.” But when she offered Joe her credit card, he put up a hand.

Mary cawed deeply in her throat, playing at annoyed, when really she felt beyond delighted. Her exuberance, markedly higher than when she walked in, had something to do with the tall man, who watched her in apparent amazement. She took a twenty from her wallet and put the bill in the tip jar, a huge glass pickle container three-quarters full of cash and change.

“Well …” Damba said. Following Mary’s lead, he took a ten-dollar bill from his wallet and dropped it into the jar.

Good man.

She stopped herself from putting a hand on his forearm to direct him out of the way because she didn’t like when men placed their uninvited hands on her, as they so often did. Instead, she took a small step forward that forced him backward until they were wedged between a table and a wall where they waited for their orders. Now very close to him, she relaxed into the vibe he exuded—protecting rather than attacking. Again his scent drifted toward her, of rich earth mingled with—

“Asher!” Joe called.

Mary scooped a finger around the back of her neck to wipe away perspiration. “Do you like discount cards?”

Damba laughed, but in apparent enjoyment rather than ridicule. She thought of retracting the strange question, then didn’t, because she never apologized for asking questions. And this time, her inquiry somehow felt dire. As though the subject explained who she was, a person who took nothing for granted and had accrued the reserves to never again be at the mercy of anyone with more money or power.

“I do,” he said.

He seemed to be telling the truth. She could tell because she’d stared into so many lying eyes. Of men who thought their charm would win a quick roll with her, a tall, slender, still something of a looker chick. Men—meaning white guys because she’d never dated a Black guy—under the assumption females fell for flattery. Assholes all, except maybe for the firefighter whom she’d loved for a minute until he let fly his opinions about this and that. She didn’t need someone who embraced the ignorance she’d grown up with when her drunk dad’s friend talked smack about people they didn’t know.

But this guy.

Suddenly nervous, she told herself to calm down. This was nothing more than a harmless lunchtime game.

Smiling, she leaned toward him and whispered. “If that’s the case, what other discount cards do you have?”

“Damba and Mary!” Joe yelled.

Mary’s shoulders jumped. She handed Damba her chip bag and soda can and went to the counter. She scooped up the two plastic baskets filled with layers of tissue paper to absorb the grease of the steaming sandwiches. She nodded toward two empty bar stools along a counter running the length of the front window. Damba moved sideways between the tables. Mary followed. She took off her raincoat and threw the garment over the back of her stool. Damba unhurriedly took off his suit jacket and positioned the coat on the back of the seat. Slender waste. Pristine white shirt. A colorful tie of black, orange and cobalt blue rather than some boring striped thing. And his black shoes: quality. This guy must be a spender. She would almost certainly win this discount card game.

She hooked her heels over the stool wrung. When her knees touched his, she felt the pressure, though in a good way, like sitting hip-to-hip with someone comfortable. She picked up the chip bag and pulled apart the top. She reached for a Cheeto, but then stopped.

“We’d better shake before my fingers turn orange,” she said.

He accepted her hand with a smile, his skin dry and warm, despite a day of wet spring chaos.

“It is nice to meet you, Mary.” He bowed his head slightly.

Unwilling to let go of his hand, she gently turned over his wrist, a move he allowed, to better see the small silver cufflinks shaped like—

“Uganda,” he said.

“Is that where you’re from?”

He nodded. “A long time ago.” His wistful tone suggested her question threatened this warm moment.

So she handed him a Cheeto. “Now let’s see what you got.”

He smiled, and the melancholy washed away. He accepted the snack. “So you think you’re going to win, eh? It is dangerous to be cocky.”

“I’m never cocky,” she said. “Just sure.”

He laughed hard enough his shoulders jogged, a motion and tone that implied he understood the difference. Cocky results from insecurity, whereas surety stems from confidence and experience. He popped the Cheeto into his mouth and chewed while pulling out his wallet. Considering she had just met this guy, she took a moment to pocket anything from her wallet that might reveal her personal information: driver’s license; health insurance card; list of emergency numbers; photos of Kathleen’s son and daughter, who called her Aunt Mary. She watched to see if he pulled out any photos of a wife or children, but he didn’t. Her stomach fluttered. How ridiculous.

As they talked and ate, her peripheral vision picked up movement outside of the window. Shreds of newspaper and other debris whirled and rolled down the crowded city street as pedestrians kept their chins tucked against the flying grit. The elevated trains passed by, shaking the building as they thundered along on their steel trestles. Car and truck horns blared despite the predictable stop-and-go traffic.

But inside, she felt warm as she chewed while wiping grease from her chin. She and Damba talked and laughed and laid down their discount cards one-by-one, making up the rules as they played. She still couldn’t believe she had found someone as frugal as herself.

When he placed a Starbucks loyalty card on the counter, Mary said, “You like coffee?”

“Love it. But I don’t drink it.”

“Why?”

“That is a long story.” Rather than explain, he rifled through his remaining cards.

Born to push, Mary wanted to do so now, and normally would. But again she sensed the need to back off, lest she push him toward that sad, far away place from which he might not return this time.

So she said, “If you don’t get coffee there, what do you get?”

“Tea.”

“Let me guess. Strong and black.”

He smiled and nodded. “Strong and black.”

Which she understood because sometimes you don’t want sugar to cover the bitter.

At some point they decided airline mileage programs wouldn’t count because neither of them knew their total points. Their respective Walgreens cards canceled one another out. When Damba presented his Dick’s Sporting Goods card, Mary frowned. He got her on that one because she was not at all sporty.

“What sport do you play?” she said.

“Football, by which I mean soccer. And basketball. And you?”

She let out a breath. Do be serious. “I walk a lot, though breathing and eating take effort too.”

Mary set down an Art Institute of Chicago membership card, an investment that paid for itself because she visited whenever she had time.

“Sometimes I imagine seeing my brother’s work there,” she said, realizing how many years had passed since she had mentioned him.

“Is he an artist?”

“Would have been. He died in a car accident in high school.”

When Damba appeared ready to ask another question about her family, or what was left of it, she said, “Do you have a CTA pass, or don’t you use public transportation?”

“I use it—”

“Though you live in—”

“Lake Forest.”

Mary lowered her chin, as befitting a once-poor girl looking with derision upon someone from the posh North Shore suburb along Lake Michigan.

He laughed. “It is not like that. I would bet you do not have one of these.” He produces a membership card to the Swahili Institute of Chicago. “It gets me into programs for a discount.”

“What programs?”

He shrugged. “Just, programs.”

“You never use it.”

He laughed.

She laughed, too, knowing you’re not supposed to laugh at your own jokes. But fuck that. She spent too much of her youth being serious. Let funny be funny.

“Well I’d like to congratulate you on playing a pretty good game so far, but my guess is I’ve got you with this one.” Mary dramatically set down her South Loop Dart League membership card. “Gets me a discount on drinks at the bars that sponsor our games.”

“You play darts?”

“Got me through college. Well, that and a scholarship, a dozen menial jobs, ramen noodles and caffeine.”

He stared at the card as though in wonder. Then he nodded. When he looked at her with his dark eyes, he did so in an oddly serious way. “I believe you’re right. You win.”

“I always do.”

His momentary solemnity crumbled into a laugh. “Somehow I have no doubt about that.”

Suddenly their time together seemed at risk of ending, the feeling chill as the slashing wind outside.

“I could use the card for you,” she said. “To get you a discount on a drink. If, that is, you’re not married or going out with anybody. I don’t want some angry woman after me.”

He again considered her. With respect for sure, but behind that, a fire that caused her cheeks to flush. As though she stood in front of him naked and he knew he should look away but couldn’t.

“I—” He smiled a little. “I am not often without words, but you seem to take them from me.”

He looked down.

She waited.

He looked up at her. “All right.”

While her heart bleated like a happy lamb, her body responded like a woman who’d been too long without touch. Maybe that was all this would lead to, a fleeting and physical liaison, like every relationship she’d ever had. Maybe she didn’t deserve more. Maybe some people were too damaged by their youth for anything deeper and more permanent.

“But don’t ask me to play basketball,” she heard herself say.

He laughed, then suddenly glanced at his watch. “I am sorry, but I have to go. I have to give a speech in fifteen minutes.”

As he stood and pulled on his suit coat, she fished in her bag, trying not to look hurried, which implied desperation. She pulled out a small gold case with her name inscribed on top. Opening the case, she took out her business card, which she slid along the counter to him.

He picked it up and held the light gray card in both hands.

He looked at her. “A lawyer. Now it makes sense.”

“What does?”

“Your skill at maneuvering me,” he said, his tone one of admiration, rather than the normal contempt voiced by non-lawyers.

A deep warmth filled her chest. “And what is it you do that requires you to give speeches on a Tuesday afternoon?”

He took a business card from his wallet and handed it to

her. She read:

Damba Rugundi

University of Chicago

Professor of Law

Dean of the Human Rights Institute

Counsel for Human Rights International

If she knew how to whistle, she’d whistle a holy shit. He not only had an Oscar-winning list of credentials but taught at her law school alma mater.

Somehow maintaining her practiced nonchalance, she said, “Human rights, ay? Hopefully you don’t have any ruthless dictators after you.”

He tilted his head with an expression absent of any joke. He pulled a lanyard from his suit coat pocket and placed it around his neck. The attached badge read International Law and Society Conference along with his name and Keynote Speaker.

Given the non-answer, she said, “You do have a ruthless dictator after you?”

He put his hands in his pockets and considered her. “We all have our detractors.”

“But there’s a difference between detractors and people who want to kill you.”

“In my experience, very little of what’s worthwhile in life is gained within the confines of security.”

Her eyes narrowed a little. “That in your speech?”

Though he smiled, the curve slowly released into a line of resignation. “I had planned to talk about one thing but instead will talk about the student from my university. She was the one at the safari camp in Uganda—”

“Oh shit.”

The story had been all over the news. The camp had been attacked only days ago by a militia that killed fourteen tourists. The young woman hid to avoid capture. Damba licked his lips. “Yet another shame for my country.”

Mary remained quiet in the face of his obvious pain. While she’d read about the recent attack, she’d quickly forgotten most of the story, which had fallen into the category of yet another killing in yet another country known for senseless acts of violence.

“Uganda has its militias,” Mary said. “We have our Timothy McVeighs.”

Damba nodded, but seemed unconsoled by reference to the young American who had blown up an Oklahoma City federal building only four years ago, killing 168 people.

Damba pulled his hand from his pocket and smiled. “Thank you for brightening my day.”

They shook, then simply held hands for a long moment.

When he released, he did so slowly.

“I look forward to that discount drink,” he said. “Then maybe afterward we can get some muchomo.”

“Which is?”

“Barbecue. My favorite is goat.” He smiled, turned, walked away and pushed out into the ferocious air that pulled at his coattail and snapped his tie back over his shoulder, as if to strangle him.

And where Mary had felt safe when she entered, she now felt unsafe, and in the most confusing way possible. Energized, on edge, finally awake. Finally ready, though for what she didn’t know.